Vision screening using evidence-based tools and procedures is an efficient and timely way to

- identify children with possible vision impairments;

- educate parents and caregivers about the importance of vision screening and their role in arranging and attending eye examinations for their children;

- refer identified children to eye care professionals for comprehensive, confirmatory eye examinations, diagnosis, initial treatment, and ongoing follow-up care; and

- help parents and caregivers to understand the importance of following the eye care professionals’ treatment plans.

Yet, children receive appropriate vision screening with evidence-based tools and procedures, conducted by formally trained and certified screeners, depending on where they live and which preschools, Head Start programs, or schools they attend. These discrepancies lead to inconsistencies that can drive inequality in children’s vision and eye care in the United States.

Up to 1 in 17 preschool-aged children, 1 in 5 Head Start children, and an estimated 1 in 4 school-aged children has an undetected and untreated vision disorder that can interfere with their ability to develop properly and perform optimally in school.

Vision disorders that are not found and treated early can interfere with learning. Children can fall behind in school, show behavior problems in the classroom, lag behind other children in school and reaching developmental milestones, and even have permanent vision loss.

Prevent Blindness recommends a continuum of eye care for children to include both vision screening and comprehensive eye examinations. All children, even those with no signs of trouble, should have their eyes and vision screened at regular intervals. Five steps should occur to identify and treat children with vision disorders:

- Parents/caretakers understand the importance of vision screening and arranging and attending an eye examination appointment if vision screening suggests a possible vision disorder.

- Children participate in routine vision screening conducted by trained and certified screeners using evidence-based tools and procedures.

- Children who do not pass vision screening are referred to their medical home or to an eye care professional (eye doctor) for a confirmatory, comprehensive eye examination, depending on the child’s insurance plan.Eye examinations are conducted by eye doctors trained and experienced in treating young children.

- Parents/caregivers arrange and take their children to the eye examination appointment.

- Parents/caregivers follow the treatment plan, including ongoing care, and share eye examination results with school nurses, Head Start personnel, and others to ensure the treatment plan is followed outside the home.

Screening children with evidence-based tools and procedures helps reduce inequality in children’s vision and eye health care in the United States.

“Amelia,” a child enrolled in Head Start did not pass a vision screening. When Amelia’s mother received a referral from the Head Start vision screening, she immediately made an appointment with an eye doctor, took Amelia to the appointment, and followed the eye doctor’s suggested treatment of buying prescription eyeglasses for the Amelia. When Amelia returned to her Head Start classroom wearing her new purple, Dora the Explorer eyeglasses, she stopped at the doorway and looked around the room. She saw a picture of giraffes on the wall. She walked to the picture for a closer look. She turned around to find her teacher and said “I didn’t know giraffes had eyes.” Her glasses allowed her to see the difference between the giraffe’s eyes and spots.

Amelia is an example of the 1 in 5 children in Head Start who has a vision disorder. Additionally, up to 1 in 17 preschool-aged children, in general, and an estimated 1 in 4 school-aged children has undetected and untreated vision disorders that can interfere with their ability to develop properly and perform optimally in school.

Vision Screening Guidance by Age

Successful vison screening requires 12 key steps before, during, and after a vision screening event. The National Center for Children’s Vision and Eye Health (NCCVEH) at Prevent Blindness created a systematic approach to finding children with vision disorders. This comprehensive approach – the 12 Components of a Strong Vision Health System of Care – is designed for anyone responsible for screening vision, including Head Start and early care and development personnel. Additionally, the NCCVEH partnered with the National Association for School Nurses (NASN) to describe this approach for school nurses. Follow this link for the Vision and Eye Health webpage on the NASN website.

Links:

- The 12 Components of a Strong Vision Health System of Care

- Head Start/ Early Head Start and Other Programs Serving Young Children: Handout – Building a Strong Vision Health System of Care

- School Nurses: NCCVEH/NASN Vision and Eye Health guidance

The vision screening piece of the 12 Components of a Strong Vision Health System of Care is designed to do the following:

- Identify children and adolescents who may have a vision disorder that could affect learning and development.

- Help to detect vision disorders when treatment is more likely to be effective.

- Refer infants, toddlers, preschool children, and school-aged children and adolescents, who either do no pass vision screening or are untestable, to eye care professionals for confirmatory eye examinations, diagnosis, treatment, and ongoing care. (Depending on the insurance coverage, primary care providers may need to make referrals.)

Screening ages according to the Bright Futures/American Academy of Pediatrics Periodicity Schedule are:

- Well-child visits beginning at 1 month through 30 months

- 3, 4, 5, and 6 years

- 8 years

- 10 years

- 12 years

- 15 years

Specific evidence-based tools and procedures are appropriate for these different age groups.

For infants from birth to the first birthday, the NCCVEH recommends observation, followed by an eye examination when indicated. The NCCVEH developed an observation/checklist tool for assessing 18 vision development milestones during an infant’s first year. This observation tool is for screening vision within 45 days of an infant’s enrollment into Early Head Start, or any program that serves and screens the vision of infants.

The document includes instructions, a page of vision development questions for each month, as well as photographs showing examples of the questions. It also contains next steps to take if a milestone is not met, including activities for parents/caregivers.

No matter the infant’s age, the screener begins with the first milestone and answers questions on each page, including the page for the infant’s current age, to ensure all vision development milestones are met. Screeners use the document each month until instrument-based screening can begin at age 1 year.

The 18 Vision Developmental Milestones From Birth to Baby’s First Birthday is copyrighted, but the document is available in the table of links to the right for free downloads to match the number of infants to be screened. As stated above, instructions are included on the cover sheet of the document, but if you have additional questions, email [email protected].

The 18 Vision Development Milestones tool is available in English and Spanish.

Posters are also available that parents and guardians can use at home to monitor their children’s key vision milestones. The posters are also available in English and Spanish.

The Bright Futures/American Academy of Pediatrics Periodicity Schedule recommends vision screening for toddlers ages 1 and 2 years.

The NCCVEH recommends instrument-based screening for toddlers ages 1 and 2 years (12 months to 36 months), according to 2016 joint guidelines for pediatricians from the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association of Certified Orthoptists, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

The NCCVEH created a Vision Screening and Eye Health for Toddlers in Head Start Programs fact sheet for the Office of Head Start’s National Center on Health, Behavioral Health, and Safety about screening the vision of toddlers ages 1 and 2 years. The fact sheet includes information on creating an Eye Care Referral List to share with families, family engagement and support for follow-up eye exams, resources to share with families during the referral for follow-up procedures, and supporting families of toddlers with visual impairment. Visit Vision Screening and Eye Health for Toddlers in Head Start Programs for more information.

The primary purpose of screening this age group is to detect amblyopia and uncorrected amblyopia risk factors, including hyperopia, myopia, astigmatism, and anisometropia.

The Bright Futures/American Academy of Pediatrics Periodicity Schedule recommends vision screening at ages 3, 4, and 5 years.

Vision screening begins with a review of signs and symptoms – or “red flags” – indicating a child may have a vision or eye health disorder that requires attention from a primary care provider or eye care professional. This external observation includes the ABCs of Observation of Possible Vision Problems that require an eye examination even if children pass vision screening.

The NCCVEH recommends either optotype-based or instrument-based screening according to 2015 guidelines from the National Expert Panel to NCCVEH for public health settings, primary care providers, early childhood agencies and educators, community organizations, and school nurses, as well as 2016 guidelines for pediatricians from the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association of Certified Orthoptists, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

NCCVEH-approved optotypes and formats:

- Single-surrounded LEA SYMBOLS® or HOTV Letters in flipcharts for a 5-foot screening distance

- LEA SYMBOLS® or HOTV letters on full threshold eye charts for a 10-foot (3 meter) screening distance

- LEA SYMBOLS® or HOTV letters presented as a single line surrounded by a rectangular crowding bar on all four sides for a 10-foot (3 meter) screening distance.

The purpose of screening the vision of school-aged children (ages 6 years through 17 years) shifts from a primary focus on prevention of amblyopia and detection of amblyopia risk factors to detection of uncorrected refractive errors and other eye conditions that could potentially impact the students’ ability to learn or to affect their academic performance. Periodic vision screening during the school years is important for school-aged children because refractive errors, such as myopia, and other visual disorders may emerge for the first time throughout these years.

The Bright Futures/American Academy of Pediatrics Periodicity Schedule recommends vision screening at ages 8, 10, 12, and 15 years.

Recommended optotypes:

- Sloan Letters when children can identify letters in random order (beginning at ages 6 or 7 years)

Instruments should be used for children and adolescents ages 6 years and older only when these children cannot participate in optotype-based screening. This recommendation will change when high quality research is available.

Some children are at a higher risk for vision disorders and should bypass vision screening and receive an eye examination from an eye care professional. At-risk conditions include:

- Readably observable ocular abnormalities, such as strabismus and ptosis

- Maternal smoking during pregnancy

- Premature birth (prior to the 32nd week of pregnancy)

- Parents or siblings with a history of strabismus or amblyopia

- Parental/guardian or teacher concern about the vision of a student

The NCCVEH recommends that children with special health care needs should bypass vision screening and receive an eye examination from an eye care professional because certain children are at a higher risk for vision disorders. At-risk conditions include:

- Systemic medical conditions with ocular abnormalities, including diabetes mellitus and juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- Neurodevelopmental disorders including autism spectrum disorder, Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, cognitive impairment, and developmental delay

Optotype-based distance visual acuity screening is recommended for children and adolescents, beginning at age 3 years.

Charts and Computer Software

Multiple eye charts for optotype-based screening are available for purchase, but not all charts are alike. Some are appropriate because they are standardized; others are inappropriate because they are not standardized. The optotypes selected and the layout of optotypes on an eye chart can negatively affect visual acuity scores obtained, meaning screeners could over-refer or under-refer children. Appropriate charts are standardized.

If an eye chart includes a 20/32 line, it is likely standardized. If an eye chart includes a 20/30 line, it is likely not standardized. Most standardized charts are used at a 5- or 10-foot screening distance, not 20 feet.

Refer to Non-NCCVEH Recommended Vision Screening Tools (Appendix A) for images of inappropriate charts that are no longer recommended because they are not based on evidence or standardized. Charts no longer recommended include:

- Snellen charts

- Allen Pictures

- Tumbling E

- Lighthouse (house, apple, umbrella)

- Kindergarten Eye Chart (sailboat as first optotype at the top of the chart)

Computer-based screening is acceptable if programmed to present screening methods and optotypes that have been validated in children.

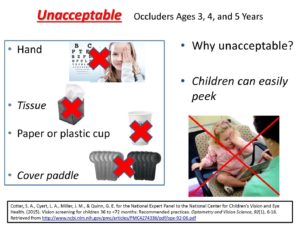

Occluders

Specific occluders to cover an eye during vision screening to prevent peeking are recommended.

Distance Vision Screening

The NCCVEH recommends distance vision screening as a preferred practice for children and adolescents participating in routine and mass vision screening, beginning at age 3 years.

Distance vision screening is an option, along with instrument-based screening, for children ages 3, 4, and 5 years.

Near Vision Screening

The NCCVEH does not recommend near visual acuity screening as a preferred practice for children and adolescents. Insufficient evidence exists to support or specifically recommend its use in routine and mass vision screening. As new research emerges, the NCCVEH will review the role of near vision screening in combination with other vision screening tests.

Instrument-based screening refers to using automated autorefractors or photoscreening devices to provide information about the eyes that could affect vision, including refractive errors and eye misalignment. Instrument-based screening does not provide visual acuity information.

Instrument-based screening is useful for shy, non-communicative, or pre-verbal children.

For toddlers ages 1 and 2 years (up to 36 months), the NCCVEH recommends instrument-based screening according to 2016 guidelines for pediatricians from the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association of Certified Orthoptists, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

For children ages 3, 4, and 5 years, the NCCVEH recommends instrument-based screening as an option to optotype-based vision screening according to 2015 guidelines from the National Expert Panel to NCCVEH for public health settings, primary care providers, early childhood agencies and educators, community organizations, and school nurses.

Instruments should be used for children and adolescents ages 6 years and older only when these children cannot participate in optotype-based screening. This recommendation will change when high quality research is available.

Visual acuity testing machines or mechanical devices similar to those used at motor vehicle testing facilities screen for distance visual acuity. Some also screen for near visual acuity and other visual functions. Machines (not to be confused with instruments that do not measure visual acuity) use a variety of letter or symbol slides that may include non-recommended optotypes. Such machines prevent observation of a child’s face and eyes during screening. Child cooperation can be problematic when screening young children.

No national guidelines support machine vision screening for children and adolescents in school and community settings.

The NCCVEH does not recommend the use of machines as a preferred practice for children and adolescents. Insufficient evidence exists to support its use in routine and mass vision screening. As new research emerges, the NCCVEH will review the role of machines as a vision screening approach.

Stereoacuity screening is conducted to determine if the eyes are working together to perceive a 3-dimentional object. If the eyes are not working together, the brain is unable to blend separate images from each into one image.

The NCCVEH does not recommend stereoacuity screening as a preferred practice for children and adolescents. Insufficient evidence exists to support its use in routine and mass vision screening. As new research emerges, the NCCVEH will review the role of stereoacuity screening in combination with other vision screening tests.

If you are required to conduct stereoacuity screening, the National Expert Panel to the NCCVEH recommends using the PASS II test.

The NCCVEH does not recommend color vision deficiency screening as a preferred practice for children and adolescents. Insufficient evidence exists to support its use in routine and mass vision screening. As new research emerges, the NCCVEH will review the role of color vision deficiency screening in combination with other vision screening tests.

A 2007 Vision in Preschoolers Study involving Head Start children found that the percentage of children with vision problems was at least 2 times higher for untestable children than for children who passed vision screening.

Children who cannot begin or complete vision screening, to provide screeners with pass/refer results, are considered “untestable” or “unable”.

The NCCVEH describes untestable children as children who

- are often inattentive during the screening activity,

- uncooperative during vision screening,

- will not allow one eye to be covered for monocular visual acuity screening, or

- do not appear to understand the screening task.

An untestable result is not a failed vision screening. A child who is considered untestable during vision screening should either receive rescreening or a referral for an eye examination

No national vision screening guidelines recommend rescreening children and adolescents who do not pass vision screening. However, the National Association for School Nurses’ Principles for Practice for Vision Screening and Follow-Up recommends rescreening all students who do not pass vision screening within 2 to 4 weeks and no later than 6 weeks.

The NCCVEH recommends rescreening before referring untestable children for eye examinations.

Until national guidance is available for rescreening children and adolescents who do not pass vision screening at Head Start or in school and community settings, screeners could use the NCCVEH guidelines for rescreening untestable children.

The NCCVEH recommends rescreening untestable children aged 3, 4, and 5 years

- the same day, if feasible, or

- as soon as possible, but not later than 6 months.

The NCCVEH recommends referring untestable children who do not pass or remain untestable during rescreening for an eye examination by an eye care professional trained and experienced in working with young children.

Untestable Children and Rescreening Guidelines for Children ages 3, 4, and 5 Years

In addition to vision screening, it is critical that key data is collected in order to develop a surveillance system.

It is also important that states and the federal government develop performance measures for children’s vision and eye health.

Data Collection Recommendations

Performance Measure Recommendations

For answers to questions regarding vision screening by age, contact P. Kay Nottingham Chaplin, EdD, at [email protected]

American Academy of Ophthalmology. (2017). Pediatric eye evaluations Preferred practice pattern I Vision screening in the primary care and community setting II. Comprehensive ophthalmic examination. Retrieved from http://www.aaojournal.org/article/S0161-6420(17)32958-5/pdf

Block, S., & Baldonado, K. (2018). Staying Focused on Children’s Vision: Leveraging Results from the 2016-2017 National Survey of Children’s Health. Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs. Arlington, VA.

Bruce, A., Kelly, B., Chambers, B., Barrett, B. T., Bloj, M., Bradbury, J., & Sheldon, T. A. (2018). The effect of adherence to spectacle wear on early developing literacy: A longitudinal study based in a large multiethnic city, Bradford, UK. BMJ Open, 8(6), 021277. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021277

Cotter, S. A., Cyert, L. A., Miller, J. M., & Quinn, G. E. for the National Expert Panel to the National Center for Children’s Vision and Eye Health. (2015). Vision screening for children 36 to <72 months: Recommended practices. Optometry and Vision Science, 92(1), 6-16. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4274336/pdf/opx-92-06.pdf

Cotter, S. A., Varma, R., Tarczy-Hornoch, K., McKean-Cowdin, R., Lin, J., Wen, G., Wei, J., Borchert, M., Azen, S. P., Torres, M., Tielsch, J. M., Friedman, D. S., Repka, M. X., Katz, J., Ibironke, J., Giordano, L., & Joint Writing Committee for the Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study and the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study Groups (2011). Risk factors associated with childhood strabismus. The Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease and Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease studies. Ophthalmology, 118(11), 2251–2261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.032 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3208120/pdf/nihms309568.pdf

Donahue, S. P., Baker, C. N., & AAP Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, AAP Section on Ophthalmology, American Association of Certified Orthoptists, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Ophthalmology. (2016). Procedures for the evaluation of the visual system by pediatricians. Pediatrics, 137(1), e20153597. Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/early/2015/12/07/peds.2015-3597.full.pdf

Fleming, R., Schantz, S., Kimel, L. S., Mazyck, D., & Murphy, M. K. (2016). Principles for practice: Vision screening and follow-up. Silver Spring, MD: National Association of School Nurses.

Gaiser, H., Moore, B., Srinivasan, G., Solaka, N., & He, R. (2020). Detection of amblyogenic refractive error using the Spot Vision Screener in children. Optometry and Vision Science, 97(5), 324–331. https://doi.org/10.1097/OPX.0000000000001505

Joint Clinical Practice Guideline Expert Committee of the Canadian Association of Optometrists and the Canadian Ophthalmological Society, Delpero, W. T., Robinson, B. E., Gardiner, J. A., Nasmith, L., Rowan-Legg, A., & Tousignant, B. (2019). Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for the periodic eye examination in children aged 0-5 years in Canada. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology, 54(6), 751–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjo.2019.09.003

Kara, C., & Petriçli, İ. S. (2020). Comparison of photoscreening and autorefractive screening for the detection of amblyopia risk factors in children under 3 years of age. Journal of AAPOS, 24(1), 20.e1–20.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaapos.2019.09.020

Nottingham-Chaplin, P. K., Baldonado, K., Bergren, M. D., Lyons, S. A., Murphy, M. K., & Bradford, G. (2020). 12 Components of a strong vision health system of care: Part 3 – Standardized approach for rescreening. NASN School Nurse, 35(1), 10-14.

Nottingham-Chaplin, P. K., Baldonado, K., Bergren, M. D., Lyons, S. A., Murphy, M. K., & Bradford, G. (2019). 12 Components of a strong vision health system of care: Part 2 – Vision screening tools and procedures and vision health for children with special health care needs. NASN School Nurse, 34(4), 195-201.

Nottingham Chaplin, P. K., Baldonado, K., Dewey Bergren, M., Lyons, S. A., Murphy, M. K., & Bradford, G. E. (2019).12 components of a strong vison health system of care: Components 1 and 2 – Family education and comprehensive communication/approval process. NASN School Nurse, 34(3), 145-148.

Nottingham Chaplin, P. K., Baldonado, K., Cotter, S., Moore, B., & Bradford, G. E. (2018). An eye on vision: Seven questions about vision screening and eye health-Part 4. NASN School Nurse, 33(6), 351-354.

Nottingham Chaplin, P. K., Baldonado, K., Cotter, S., Moore, B., & Bradford, G. E. (2018). An eye on vision: Five questions about vision screening and eye health-Part 3. NASN School Nurse, 33(5), 279-283.

Nottingham Chaplin, P. K., Baldonado, K., Cotter, S., Moore, B., & Bradford, G. E. (2018). An eye on vision: Five questions about vision screening and eye health-Part 2. NASN School Nurse, 33(4), 210-213.

Nottingham Chaplin, P. K., Baldonado, K., Bradford, G. S., Cotter, S., & Moore, B. (2018). An eye on vision: Five questions about vision screening and eye health. NASN School Nurse, 33(3), 146-149.

Nottingham Chaplin, P. K., Baldonado, K., Bradford, G. S., Cotter, S., & Moore, B. (2018). An eye on vision: 20 questions about vision screening and eye health. NASN School Nurse, 33(2), 87-92.

Nottingham Chaplin, P. K., Baldonado, K., Hutchinson, A., & Moore, B. (2015). Vision and eye health: Moving into the digital age with instrument-based vision screening. NASN School Nurse, 30(3), 154-60.

Nottingham Chaplin, P. K., Marsh-Tootle, W, & Bradford, G. E. (2015). Navigating the path of children’s vision screening: Visual acuity, instruments, & occluders. Retrieved from https://www.schoolhealth.com/media/pdf/NavigatingVisionScreening.pdf

Nottingham Chaplin, P. K., Ramsey, J. E., & Baldonado, K. (2014). Children’s vision health: How to create a strong vision health system of care. Exchange, 36(3), 36-41.

Nottingham Chaplin, P. K., Ramsey, J. E., & Baldonado, K. (2014). Children who should bypass vision screening and go directly to eye exam. Exchange, 36(3), 38.

Nottingham Chaplin, P. K. (2014). National and international guidelines for standardized eye chart design. Exchange, 36(3), 39.

Nottingham Chaplin, P. K., & Bradford, G. E. (2011). A historical review of distance vision screening eye charts: What to toss, what to keep, and what to replace. NASN School Nurse, 26(4), 221-227.

Prevent Blindness. (2019). Developing a consensus for children’s vision and eye health programs. https://nationalcenter.preventblindness.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/06/VSConsensusStatementRev2019.pdf

Prevent Blindness. (2015). Prevent Blindness position statement on school-aged vision screening and eye health programs. Retrieved from https://preventblindness.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Prevent-Blindness-Statements-on-School-aged-Vision-Screening-Approved-8-2015.pdf

Stein, J. D., Andrews, C., Musch, D. C., Green, C., & Lee, P. P. (2016). Sight-threatening ocular diseases remain underdiagnosed among children of less affluent families. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 35(8), 1359–1366. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1007 Retrieved from https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1007?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub++0pubmed&

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2017). Vision screening in children ages 6 months to 5 years (Evidence Synthesis No. 153). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK487841/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK487841.pdf

Ying, G. S., Maguire, M. G., Cyert, L. A., Ciner, E., Quinn, G. E., Kulp, M. T., Orel-Bixler, D., Moore, B., & Vision In Preschoolers (VIP) Study Group (2014). Prevalence of vision disorders by racial and ethnic group among children participating in head start. Ophthalmology, 121(3), 630–636. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4128179/pdf/nihms603561.pdf

Links and Downloads

18 Vision Development Milestones From Birth to Baby’s First Birthday (English)

18 Vision Development Milestones From Birth to Baby’s First Birthday (English, fillable pdf)

18 Vision Development Milestones From Birth to Baby’s First Birthday (Spanish)

18 Vision Development Milestones From Birth to Baby’s First Birthday (Spanish, fillable pdf)

18 Vision Developmental Milestones Poster (English)

18 Vision Developmental Milestones Poster (Spanish)

2016 guidelines for pediatricians from the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association of Certified Orthoptists, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology

A Guide to Vision Health for your Newborn, Infant, and Toddler (English)

A Guide to Vision Health for your Newborn, Infant, and Toddler (Spanish)

A Guide to Vision Health for your Newborn, Infant, and Toddler (Chinese)

Ages When Vision Screening Should Occur

Children who Should Bypass Vision Screening for an Eye Examination

Children who should bypass vision screenings and go straight to an eye exam

(Handout from Reena Patel, OD, FAAO, for the Year of Children’s Vision Initiative)

Data Collection Recommendations

Evidence-based Vision Screening Tools and Procedures

National Webinars with the National Webinar With the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness

Vision Screening Tools for Very Young Children

Your Vision Screening and Eye Health Program

Non-NCCVEH Recommended Vision Screening Tools for Ages 3 to 18 Years (Appendix A)

Tips for Appropriate Eye Chart Design

Optotype-Based Screening for Children 36 to <72 Months

Performance Measure Recommendations

Prevent Blindness Children’s Vision Screening Certification Course

Prevent Blindness Statement on School-Aged Vision Screening and Eye Health Programs

Referral Criteria for Optotype-Based Screening

Signs of Possible Vision Problems in Children

Signs of Possible Vision Problems in Children – Spanish – Signos de problemas de visión posibles en niñosStereoacuity Testing

Untestable Children and Rescreening Recommendations

Vision Screening and Eye Health for Toddlers in Head Start Programs

Vision Screening and Eye Health for Toddlers in Head Start Programs (PDF)